Veteran Suicide Prevention / Crisis HELP

then press 1

then press 1

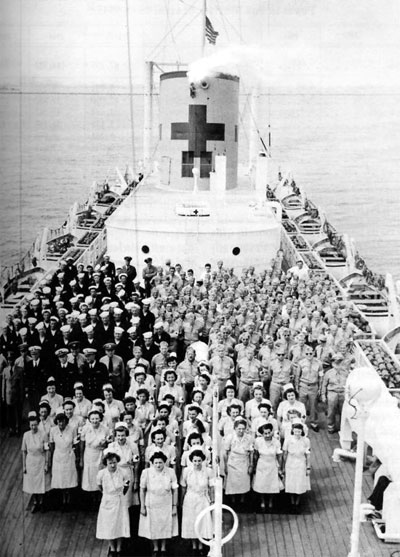

I adore this 2011 painting of "my ship," the USS Comfort, by Frank Walsh.

I was honored to be consulted for it, though the artist had done so much homework he almost knew more than I did. We spoke a few times at length over the phone. I know he was surprised how much I could remember and the details, but I'm sure that would be true for anyone who spent time aboard the Comfort. She was such a beautiful ship. Frank really captured her. I have used this image for my desktop image on my laptop for 12 years and my son printed a large version he hung on the wall that I see from my bed every morning and night. I never grow tired of this beautiful painting and show it to all my guests.

Editor's note: Mom's carried around 5 boxes of memorabilia she collected during the years of war. Year-after-year we planned on sorting them out, but every time we settled in the for the Winter and opened the boxes, we were both overwhelmed. A friend volunteered to help Mom/Doris get a scrapbook together. It took a year-and-a-half working for a couple of hours each week to get the scrapbook finished. And with it, many stories I heard as a child are updated with details and corrections, because Doris' memory, even at 103, is prodigious. She remembers in great detail nearly every minute of those times.

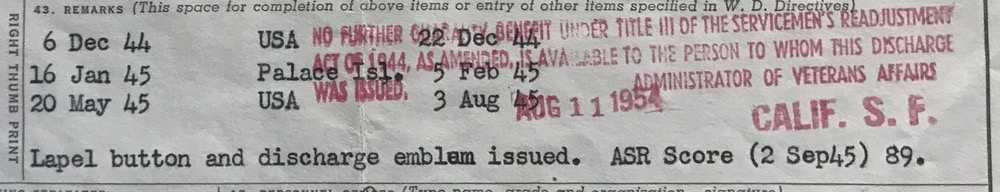

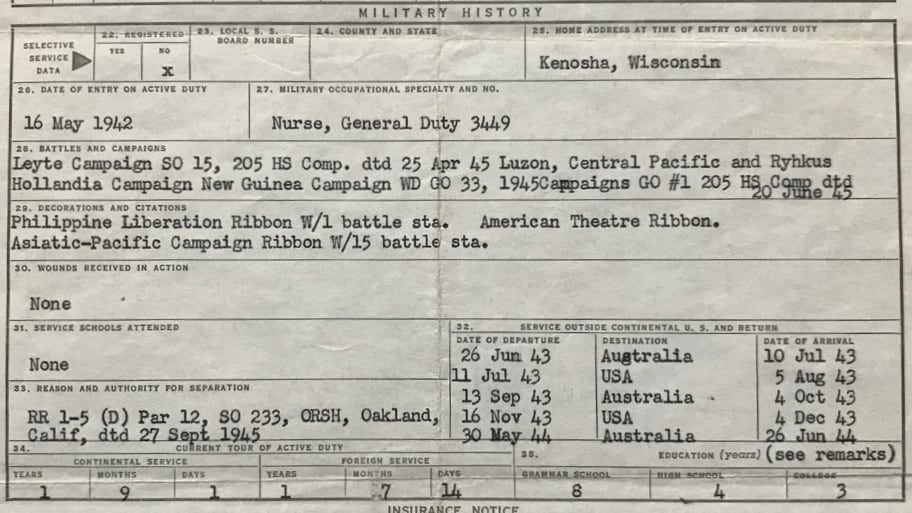

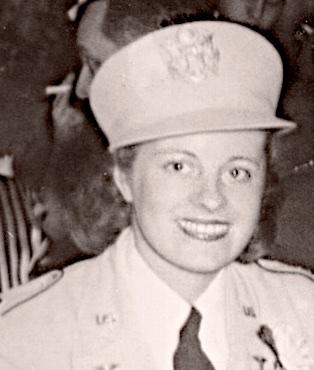

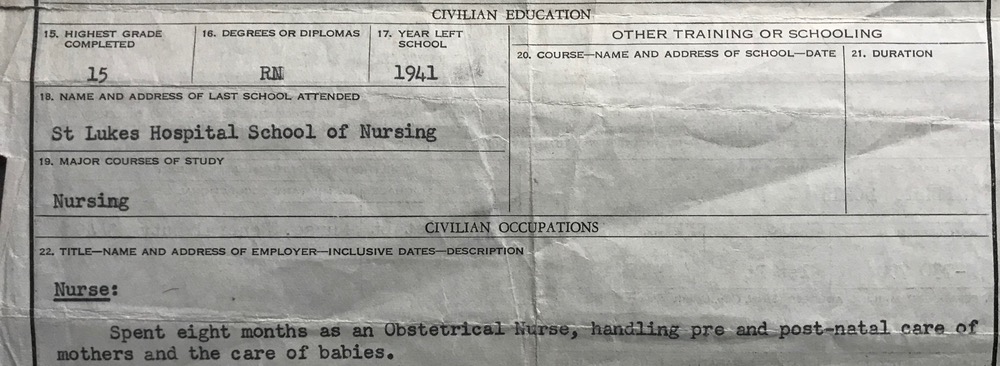

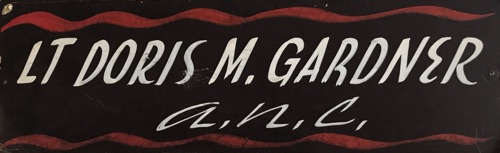

For the duration of World War II, Doris Gardner performed the duties of a Lieutenant (2nd & 1st) in the Army Nurse Corps. While in high school, Doris had decided to become an airline stewardess to travel the world. In those days a flight attendant needed nurse's training, so off she went. By the time she graduated, war was on the horizon. Doris got her wish to travel the world, but on a lot more than an airplane.

Onboard the newly commissioned U.S.S. Comfort, while docked in the Bay of Okinawa, Doris Gardner and Mary Rodden, best friends from small towns in Wisconsin, would sneak out on to the forbidden upper deck to watch the war.

Beyond the low lying hills the battle was raging. Fierce thunder and blood-red flashes filled the sky twenty-four hours a day. All around them in the waters of the Bay of Okinawa the battle was in its fore-stages. Whole ships sunk on either side of the new, bright-white hospital ship. The vessel rocked violently, threatening to spill them overboard as whole ships went down on both sides of them.

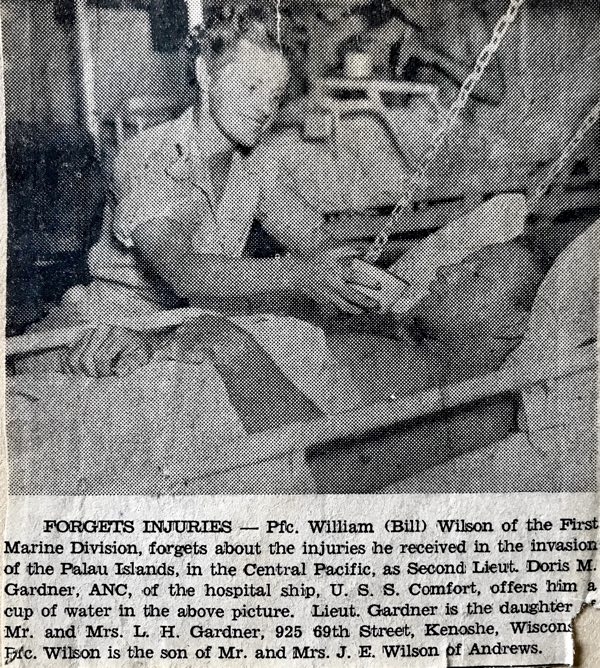

"A ship would be berthed to our starboard. Then the ship would no longer be there. Gone. A deafening explosion. Water shooting so very high into the air. It took only an instant for the ship to sink below the water and be lost. We didn't see how there could be any survivors. Then the same would happen to our port side. We hung on for dear life as the ship herself seemed to fight being overturned."

Hidden on the off-limits deck, Doris and Mary would look out on the war. As far as the eye could see lines of ambulances stretched from the horizon, filled with dead and dying "boys" as they called them for, to those 22-year-olds, that's what far too many of them were.

From the faraway hilltop behind which the battle raged, the line of red-crossed trucks queued their way to reach the gangway of the Comfort, each truck filled with the prostrate.

Medics were busy at the gangway hauling onboard stretchers and those who could no longer walk on their own. As the ambulance drove away another took its place instantly, endlessly, until the ship was full to capacity, though the line of ambulances from the gangway to the far-away hill never diminished. When the Comfort drew in her gangways and left for hospitals in the South Pacific at Guam, Australia, New Guinea, Hawaii, the ship left the line of trucks behind.

Among the nurse, doctor and military crew friends that Lt. Gardner had made onboard, the Chaplain, Father Weilandt, had been the talk of the ship. The kindest man many had ever known, he had a special nature rarely seen in people. He left the relatively care-free, mid-sate California mission--where his grave is still marked--to volunteer for the "war effort."

Talk had gone around the ship of recommending the man for sainthood once the ship was stateside. He worked some magical power of love among the wounded and those who cared for them.

Doris, a petite 5 feet tall, 90 pound and comely woman, soon became well known and friends with many onboard. Officers were asking her for dates at every chance. She and her girlfriends devised a plan. Say yes to all the men. Go out with the first to arrive. When the others came the other girls would be ready to go.

But of lasting friendship Mom has said, "You met a man in those days, shook his hand and looked him in the eye, but only for a moment. It was always in the back of your head that he could be gone in an instant."

You loved your girlfriends. You knew all would be safe onboard. A hospital ship, when it's lights are on at least, is a safe haven.

It was not.

On the night of 28 April 1945, the ship's second trip to the bay, the Comfort drew up her gangways with more than full complement of wounded and dying. Her capacity was overstretched, adding hundreds more than she was built for. The battle was relentless in producing the wounded and dying. The surgery was, as it had been for days, working hard at the business of lopping off in amputation; sewing on in rescue; extracting bullets, shrapnel and embedded earth; attempting to relieve the sustained torture of severe burns.

The ship "set sail" and began to exit the bay.

The Comfort was an obviously new ship as observed by any who saw her. She was brightly painted and lit up at night in the prescribed manner "like a Christmas tree." And she was no stranger to being the target of combat.

In the battle of San Bernardino Straits, the Comfort had been caught between two forces firing on each other and was strafed by Japanese fighter planes. This danger was another reason being on-deck was off-limits during the war. Luckily, in that instance, the ship bore no casualties of its own, but it was becoming clearer, hospital ships were no longer protected by international law. The whispering onboard was that it was just a matter of time before the ship, too, would be hit and likely left to sink as other ships had gone down around them.

One morning months earlier, when Doris went on duty as the Comfort left the Leyte campaign in the Philippines with wounded, she was told by the ship's navigator a Japanese torpedo had narrowly missed the ship during the night. Had it struck they surely would have sunk.

The U.S.S. Comfort was becoming more vulnerable. Would they remain lit as prescribed by hospital ship behavior in international rules of war, or would they go dark and hide?

Nightly they withdrew from the beaches at Okinawa, remaining alight far out in the bay so as neither to risk themselves near battle, nor to endanger other ships by bathing them with their candlepower.

The coming and going proved to be too much for the ship and the Comfort stayed in harbor overnight, their lights out. The ship's surgery, ablaze twenty-four hours a day with ongoing shifts of nurses and surgeons, was protected deep inside the interior of the ship. Its lights did not jeopardize the safety of the ship.

The floating hospital, now loaded with the compromised, made their way out of harm's way. As they set out to sea, they passed the ships at harbor that were darkened for protection. Within half-an-hour they lit up to "full brilliance," the Comfort's six large red crosses broadcasting "safe harbor" as it left behind the darkened bay awash with death and machines of war.

The ship enjoyed a tranquil journey on the water, though inside her the medical crew was running full steam to treat and relieve the most wounded of the battle. Under a full moon the hospital ship moved gracefully, its crew and cargo glad to be leaving the tragic battle. They were headed to the land-hospital on Guam. An observer later wrote the ship was "lit up like a great city with a Red Cross in large letters" at its center.

Having survived torpedos, bombings and battle, no one expected at this stage that the red cross along her side, amidships, was about to become a target.

Now out to sea, an hour behind continued the largest sea-land-air battle in history and the last battle of World War II, the battle of Okinawa. In three months, the bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki would rain down their terror and the war with Japan would be over.

Lt. Gardner was on duty late in the evening on an aft ward caring for those coming from and heading into the nearby surgery in the center of the ship. At 8:30 she began preparing medications for those in her care. By 8:45 she finished by filling a syringe with painkiller and placing it on a tray. She opened the medicine cabinet to put the vial back. Before the door was closed, an explosion ignited behind the wall. The 92 pound, 5'0" nurse was picked up straight into the air by the concussion and thrown eight feet backward, slamming full body into the bulkhead.

She was made deaf for twenty-four hours and suffered permanent inner ear and spinal damage. The medicine cabinet and the wall to which it was attached were gone. All she could see through the smoke was a tangled mass of ruin as she peeled herself from the wall to help those who must have been much more hurt.

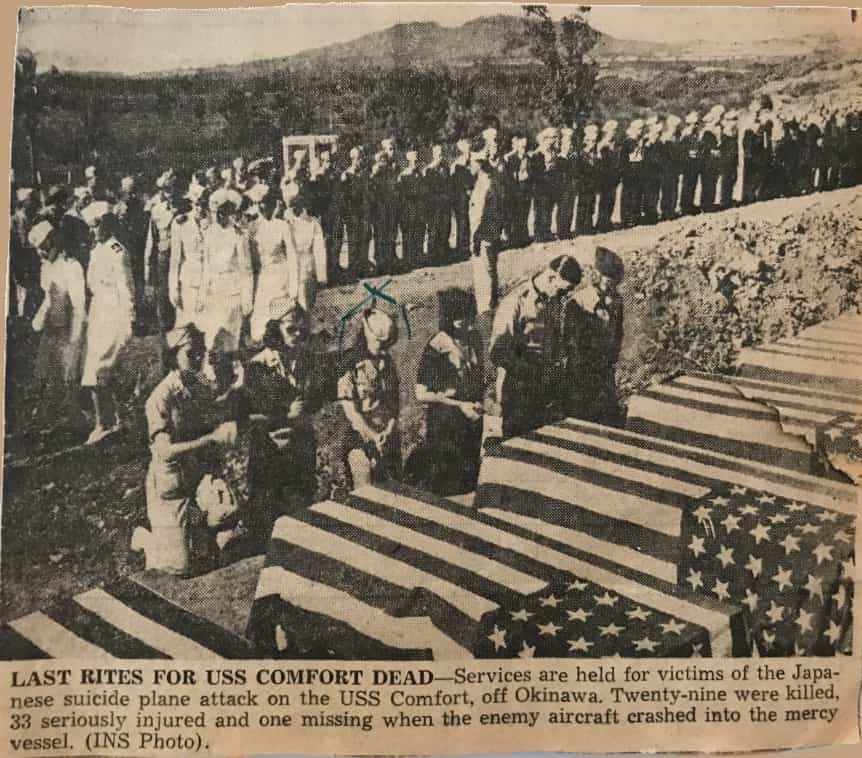

A kamikaze pilot had aimed his plane for the ship's red cross emblazoned on her side, amidships and struck right through to the core of the hospital's duties, the surgery. The four surgeons, six nurses, and wounded in surgery were killed instantly. The heart of the ship stopped beating and went dark. Thus crippled, it ground to a halt out in the ocean, by itself with no convoy or help in sight.

The nurses had talked about the small amount of lifeboats carried by the Comfort. "If there's an abandon ship, some of us are going to have to stay behind. There's not enough for the patients on stretchers and the crew. We'll have to make way for the boys."

As Gardner picked herself up off the floor, she found she had become deaf. Remarkably, the wounded were not injured in her ward, just jounced around by the blast which took the wall away closest to surgery, but no more. In shock and pain, but dertermined to perform her duties, she gathered herself together and made a quick assessment of the situation and continued as best she could the rounds she had been performing. The men were staring at her wild-eyed, knowing she had been hurt badly. They were talking to her, but she heard nothing. Her medical wardman, Sgt. Ashworth, found his way into through the twisted hot metal. As he talked to her he could see she was not herself.

"Are you all right?" he mouthed.

The men were all talking from their bunks and pointing to the spot she landed. He spoke some more to her, but she shook her head. Finally he mouthed slowly, "Abandon ship!" The Comfort was taking on water.

One of the wounded young men in her ward required oxygen to breathe. A good part of his face had been blown away by a blast in battle, though his eyes remained keen. The single tank was large enough to provde for many in the ward. If the tank had been damaged by the blast their ward would have been no more. Remarkably it remained intact. Her first thought was to turn to him. They locked eyes. She knew he could hear the abandon ship signal.

"Don't worry. I'll stay with you. I won't leave you."

Later, when she was asked about it, she said, No one should ever die alone.

Gardner would do her best to get the men who could out to the lifeboats, then remain with those who could not make it. There were not enough lifeboats even with standard capacity. She prepared herself to go down with the ship and continued to make her rounds visually, not able to leave her desk due to her back injury, checking in with hand signals each of the wounded in her surgical recovery ward.

Some time later, after assessments showed the Comfort was not taking on water as previously believed, the abandon ship alarm ceased. Doris' hearing did not return for some days, and the men had to signal to her at great length to get her to understand the alarm was cancelled.

I was in shock, dizzy, trembly and soon found that I couldn't hear anything but the roaring in my head, nor could I see too clearly. Sgt. Ashworth wrote in large print and I answered vocally. Ashworth said the abandon ship was sounding loudly. I could not hear it, but told him to get stretchers for our patients who could not walk. He just shook his head. I did not understand why and I repeated my order. He again shook his head and wrote "Can't." About 10 minutes later he said the all clear sounded. We turned my stool around and I sat propped against my desk watching my patients for about 1½ hours and then was able to make rounds and determine all was well with my patients. No one had been injured further than their original injuries.

About 0200 I walked with Sgt. Ashworth to the door of my ward and found that there was nothing forward but a gaping hole. The elevator was gone, the surgery was gone as well as the alleyway. It was impossible to go forward.

I was very fortunate to have Sgt. Ashworth as my corpsman. He was intelligent and very well trained. He could give injections and medications under minimal supervision. We had been in Naha for six days and he was well used to the routine and knew all the patients. Working together we fulfilled our medical duties, he moving about and I watching when I could, but mostly kept my head down on my desk hoping to recover from the aching I felt along my entire body.

We saw no one until the next morning at 0600. Major Silverglade, the Chief Medical Officer, stopped by the ward and I was aware Sgt. Ashworth was apparently telling him our patients were all OK, but the nurse wasn't. I saw him shaking his head. I think he was saying the nurse didn't want to bother anyone with her injuries when so many others were in dire need of care. I was giving medications at the time, so I just waved to him and he disappeared. He was a very busy man, now in charge of all surgical patients as well as his own medical patients and no surgeon aboard to assist him. He checked my ward in the daytime so I did not see him.

I rested in my bunk all the 12 hours I was off-duty, and I returned to duty that night as we were very short-handed. Six nurses had also been killed.

Father Weilandt had just left the surgery, having ministered to all as he could, wounded and staff. As he walked the deck he made his "Office of the Day," prayers for strength. He paced from fore to aft, one end to the other. As he neared the ship's center the suicide plane aimed for the largest red cross, coming in "amidship," the most vulnerable spot to sink a vessel. The pilot neither faltered nor fell short. He must have seen the Father just above the red cross as he rammed into the ship.

One would have hoped that Father would have been knocked into the water with a chance of being rescued, but Weilandt's fate was far more cruel. The plane was going fast and drove deep into the ship, creating a red-hot, burning hole of twisted metal and smoke in its wake. A large fire broke out, seen in the distance by observers. The deck below Father Weilandt's feet buckled under him and gave way. He lost his footing and fell into the burning hole. When it was safe enough to retrieve him from the fire, third degree burns covered 90 percent of his body.

And yet he lived.

Finding himself now a patient on the ship, a victim of war, in appalling pain and suffering, Father Weilandt's "special way" was not lost. Astonishingly, it increased.

Weilandt lived for two weeks, mummified in bandages wherein only a small slit at his mouth revealed the man beneath. He had been blinded and the wrappings around his head made no attempt at eyes.

Without complaint, asking after others, wanting to help, Father whispered with all of his strength, "Forgive."

The surviving nurses took their turns at making him as comfortable as possible. They knelt at his bedside in prayer, "Please, God, relieve this man's extreme agony," which agony became their own.

Soon, any movement was too painful for Father, even to shake his head "no" when asked by the surviving nurses if they could do anything for him. Within a few days Weilandt found it too painful to speak.

The ship was able to travel, limply, on its own steam. In convoy, with a full house of wounded and less than half the staff, the hospital ship made its way to Guam for what repair could be done at the limited base and to bury the 28 Army nurses and doctors, patients and navy staff who were killed instantly. The ship then limped its way to Hawaii where more who subsequently passed away en route were buried.

From Guam the ship took over a week to crawl to Hawaii. There, two weeks after the incident, Father Weilandt was relieved, finally, of his miserable condition.

The loss of six Army nurses onboard the Comfort is recorded as the deadliest attack in history on American women in uniform.

There are more stories Mom tells, those of men driven mad by war, suspended in a large cage in the hull of a ship, the only access a narrow gangway. Accompanied by two armed guards in front and back, the nurse carried her prepared medicine tray along the plank. A lurch of the ship and a fall would cause all three to topple to their deaths. From outside the bars, while guards beat the other men off, twenty-two-year-old Lt. Gardner tended the sick.

The nightmare of the helpless, disordered minds of tortured men reaching out to her through the bars haunts her dreams these seventy years later, as does the nightmare of those "boys" who jumped overboard to their suicides.

Today Mom says, "War is hell. I've seen the worst of it. War is never the answer."